Our first Learning Journey event focused on food, where we took a day long journey to find out new answers to the question ‘What will Be On My Plate in 2042?’.

We began our day at the Upper Dysart Farm, a family farm specialising in potato growing on the east coast of Angus, then travelled west across our Bioregion back to Alyth to visit Kirklandbank Farm, a small holding, producing both food and drink, then to vegetable producer Myreside Organics, also in Perthshire, before ending the day at the new community market garden of Campy Growers on the outskirts of Dundee.

Each of our hosts shared their perspectives on our food future and the challenges and opportunities of producing food in Tayside over the next 20 years.

Our multi-generational group of participants from across the Tayside included food producers, scientists from the James Hutton Institute, community climate activists and journalists. Throughout the day we wrestled with the many thorny challenges that surround food production and consumption in our Bioregion (and more widely), asked new questions of each other, shared our beliefs and began to understand some of barriers and roadblocks to the urgent systems change we need on our doorstep and beyond.

Andrew Stirling and his family have been farming their 440 acres near Lunan Bay for over 30 years. They grow, process and cook potatoes, most recently creating an innovative new additive-free mashed potato product which has been packaged in such a way as to dramatically extend its shelf life, cut the amount of food that is sent to landfill and, because it can be microwaved, is ready to eat using a lot less energy, an issue that since our visit at the end of May has become of huge concern to most people as a result of the massive escalation in energy costs.

Andrew Stirling, photo Clare Cooper

Andrew told us; “We have a lot of experience preparing vegetable for wholesalers and retailers, and for many years we supplied washed and peeled vegetables for schools and hospitals under our Stirfresh brand. Typically, you get 5 to ten days’ shelf-life on prepared food, but by vacuum sealing it when it’s cooked, which is what we are now doing, it stays fresh for up to four weeks.”

Some of Upper Dysart Farm’s products

As Andrew told us the story of how he and his family had developed what they do on their farm and showed us around, he shared his own principal concerns with regard to future food production.

In his view, the lack of education in schools about growing and preparing food and the very poor quality food children get given at school has been and continues to be a huge issue.

Additionally, the low numbers of local people who want to work on farms needed to be resolved if Tayside was to increase its food security. Andrew also said that food was too cheap, making it almost impossible for many farmers to have a viable business and that increasing the price of food whilst at the same time encouraging people to eat more healthily could be very beneficial to both producer and consumer. “What I’m saying”, he said, “is increase the price of food (and) reduce the size of a portion”. Andrew was also very aware of the mitigation and adaptation that was going to be necessary for food producers such as himself as a result of the climate crisis and was already looking at how to re-use of some of the by-products of their production processes for soil improvement and water storage.

Questions and answers with Andrew Stirling, photo Clare Cooper

In a nutshell, in addition to hearing about Andrew’s own very successful farm diversification story, and how their new food production ideas, such as the mashed potato range, were being shaped and driven by the younger generations of his family, we left with a much greater understanding of some of the severe challenges facing larger, commercial farmers like Andrew in Tayside today. From their perspective, what was going to be on our plate in 2042 would depend very much on what could be done to address the issues at the top of their list right now which were costs of production, supply chain issues and labour shortages.

We travelled west from Andrew’s farm on the beautiful Angus coast, along the Highland Boundary Fault, until we reached the seven acre small holding owned and managed by Dr Marian Bruce and Simon Montador.

Simon and Marian outside their distillery, photo Highland Boundary

Tucked into the southern flank of Alyth Hill in eastern Perthshire, overlooking the fertile Vale of Strathmore, Kirklandbank farms a small flock of Hebridean sheep, offers self-catering holidays and operates an artisan distillery, Highland Boundary, which uses hand foraged local botanicals as flavours for an award winning range of spirits and liqueurs.

Marian & Simon’s award winning spirits and liqueurs, photo Highland Boundary

Marian explained their ethos and how it informed everything they did on the farm. “What we do here and what we want to try and demonstrate is that you can create biodiversity and farming together.”

“What we do is all about being a nature friendly, regenerative business. It’s about restoring the biodiversity that should be in our landscape, supporting that, and actually using it, whilst at the same time being aware that biodiversity is absolutely the thing that we need to create because it supports the living planet that we all depend on.”

“All the products that we make in the distillery are flavours from our own woodlands. Flavours that were used hundreds of years ago and we’ve forgotten about.”

“We do a lot of research around old products and then re-invent them for the 21st century, innovating around how you extract the flavour from our wild plants. Our products are not gin. We don’t use juniper because it’s an endangered plant in Scotland. We use birch, sloe, larch, honeysuckle and are experimenting with other flavours and non-alcoholic drinks too. Everything that we pick, we pick ourselves and it’s sustainably picked so we’re only taking a small amount from each plant. We’re not defoliating the whole tree. That way the tree survives, it’ll be there next year. We can pick it again next year. So it’s about harvesting differently, thinking about the biology of what you’re doing, understanding that there are limits to what you can actually extract from our forests without then damaging them.”

Sloes on Alyth Hill, photo Clare Cooper

“So we work sustainably in terms of the picking with very strict regulation. But these botanical spirits are made across the whole of the rest of Europe. They’re called different things in different places. And it’s only in the UK that we have not made these for hundreds of years because we have become so disconnected from our landscape.”

Similarly to Andrew, Marian feels we do not pay enough for our food. “The fact is that we pay less now for our food than we have ever done in history.. we don’t value what we’re putting in our bodies enough to pay. And that’s why farmers can’t make a living.”

Also in common with Andrew, Marian had found the whole issue of packaging, and the difficulty of getting fully recyclable packaging across all aspects of production, hugely problematic. “When we were designing bottles and labels back in 2017, it was extremely difficult to have that conversation of ‘no, we don’t want plastic. No, we don’t want foiling on our label because we don’t want to use plastic.’”

You can hear more about what Marian had to say about small plots of land can be huge drivers of regeneration, the reasons that lie behind the disconnection from our wild plants in Scotland and the enormous potential of what are called ‘Non Timber Forest Products’ to be a much bigger part of ‘What Will be On Our Plate In 2042’ at this link here.

The third food producer we heard from was Organic Farmer, Antonia Ineson. Her small 2 acre plot of land, which she leases, lies just a few miles away from Marian and Simon’s in the heart of Strathmore, and because by this time the weather had turned against us, Antonia had come up to Kirklandbank to share her story with us. Her three organic polytunnels house salads and summer vegetables and she sells directly to individual customers, through Farmers Markets and to local shops and restaurants.

Antonia telling us about Myreside Organics and her work, photo Clare Cooper

She began by explaining some of the practicalities of being a market gardener on tenanted land, including the kind of tenancy agreement she has and how she resolved her accommodation issue, both very importantly enabled by Scottish Government policies. She would not have been able to set up Myreside Organics without that enabling policy framework.

Like Marian, Antonia underlined the importance of biodiversity “We have to become more diverse in what we are doing.” And like Andrew and Marian, the price of food and the financial viability of farming were big issues for her too. “The price of food is a constant issue. The pricing of what I sell. I’m torn between the issues about food quality, poverty, and inequalities. Before I did this, I worked in public health in Lothian health for years. I worked mainly on health inequalities during that time. It’s something that I am very much aware of. I’m also aware that that is not going to be solved from farming or food growing. And so what I try and do is price at what I consider a fair price. But I think it’s a huge issue.

“And financial viability. I’ve done quite a bit of interviewing organic growers and farmers. I would say if you took the subsidy away, none, well, no farming in Scotland is viable if you take the subsidy way at the moment… And the Government is almost saying more of the Westminster government, but also the Scottish government, you have to diversity to be a farmer or grower. And I think that’s true. So you need another income coming in from something else. Now, why is that true of farming and nothing else? …so a lot of small growers depend on free labour, volunteers and you know socially that’s really interesting and really valuable, it brings people into the countryside, it gets some understanding about food production. I’m not knocking it, but what other business would you expect to depend on free labour? It’s madness.”

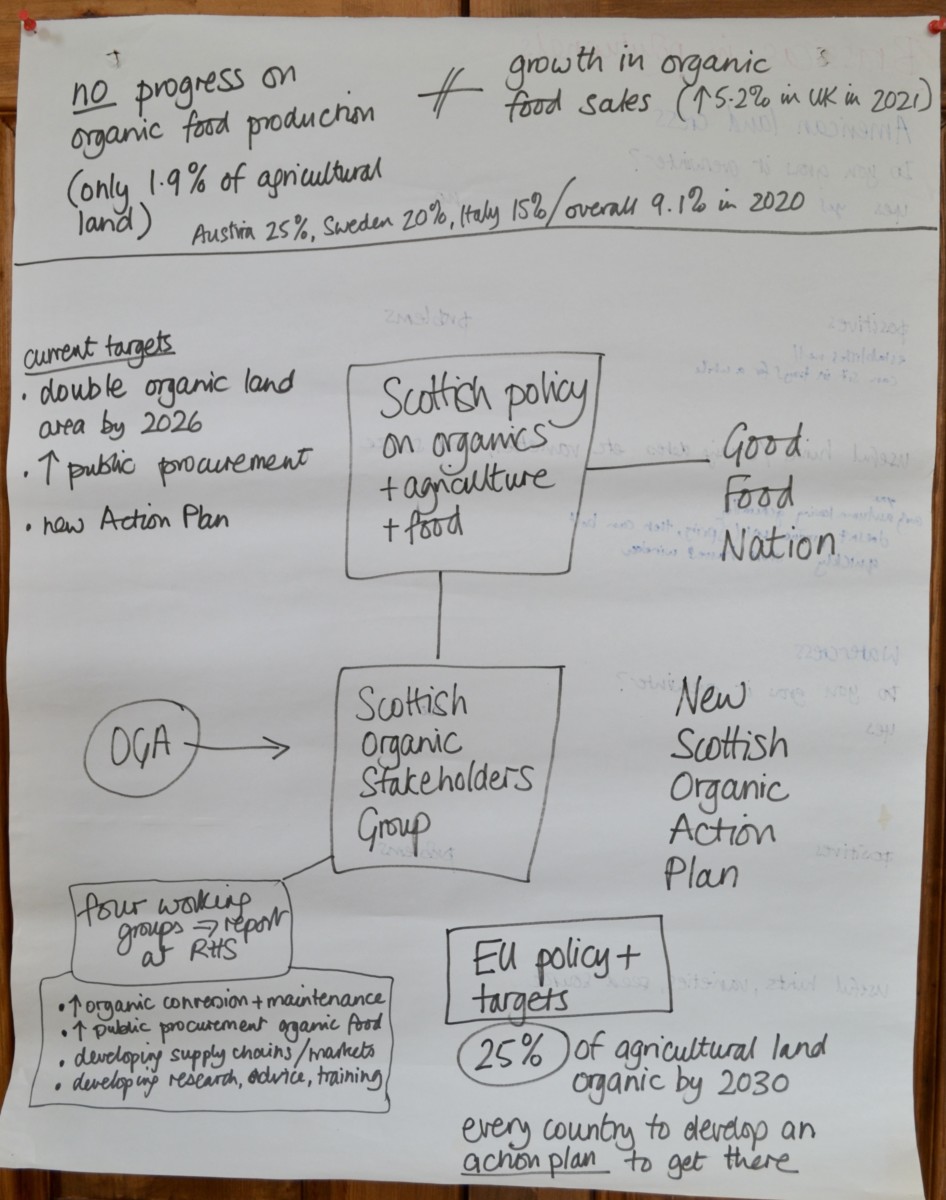

Antonia’s ‘aide memoire’ on the policy frameworks in play to advance Organics, photo Clare Cooper

What’s really important to Antonia is the links she has with other growers. “I’m part of the Organic Growers Alliance, which is a UK wide organization. We have an incredibly good Facebook group. I use that as my farms advisory service, basically. It’s a closed group, very controlled, but people involved in that are very, very experienced organic grows. And so you put a question on there, you get absolutely superb advice. If people don’t know, there’s a really good debate about what the pros and cons of things are”.

But Antonia thinks that we need a much more developed infrastructure for supporting food producers in Scotland. “We shouldn’t be depending on Facebook. It’s crazy. We should have really good institutions in Scotland which can advise people in all sorts of agriculture about the latest research. I would really love to have access to more research. I know there’s really interesting stuff going on in the Continent…I’ve been to two fantastic events. One was a Slow Food event in Turin, and the other was something called Tech & Bio, which happens every other year, which every other country in Europe pretty much sends a delegation to. They have a stand all about organics. It’s fantastic. It’s about all aspects. It’s about everything from viticulture to animal production to arable to small scale production. It includes fantastic trade stands showing the appropriate tools and mechanical stuff. Scotland wasn’t there. Why don’t we send some group to actually learn? It was over three days I think, they had something like six parallel sessions at all times of meetings, I mean, it was just amazing. There were huge numbers of young people there. It wasn’t all people of my age, over the hill and trying to keep going. It was really inspiring. And I think we need to get a Scottish delegation to the next one.”

Antonia at her farm, photo, Myreside Organics

You can read much more about what Antonia had to say about the challenges facing organic growers and organic food production more generally in Scotland by reading this edited transcript of her talk here.

Antonia’s story generated a very rich and feisty conversation about the opportunities mainstreaming local organic production could offer. This ranged from enabling a wellbeing economy, to restoring soils and biodiversity to addressing some of the major health issues of our time such as diabetes, and their cost to the NHS, to the re-population of rural Scotland. Other points made included the accumulating evidence that with the escalating cost of pesticide and fertilizer, Organics could actually become more economically viable than current commercial farming and the huge opportunities there were for communities to drive the system change needed by creating new infrastructure that could support more local Organic production such as CIC’s (Community Interest Companies).

We left for our last site visit, much better informed about how Organic food production could help ensure that we had more local, and much better quality food on our plate in 2042.

Campy Growers is a new community market garden that lies in Camperdown Park on the outskirts of one of the Tay Bioregion’s two cities, the City of Dundee. With a population of just under 150,000 people, Dundee is one of Scotland’s most deprived cities with the number of people going hungry and struggling to access food ranking amongst the highest in the country.

Kate Traherne introducing Campy Growers, photo Clare Cooper

Kate Traherne and Beverley Searle, from the project’s organising committee, welcomed us to their 11 acre site explaining: “As you can see we are just starting out but we have a grand vision for this south-facing slope to grow lots of food, as well as helping people to learn how to grow their own.”

“This idea has emerged from the council’s push to provide community growing spaces all over Dundee as one of the recommendations that came out of the Dundee Fairness Commission’s first report in 2016, “A Fair Way To Go” (see p.32).”

“This report lays out the multiple crises that faced Dundonians several years ago and it has only got worse with Dundee consistently at the bottom of many metrics of human health. We find ourselves now in a critical pinch point with poverty, poor nutrition verging on starvation, social breakdown, pandemic, exploitative capitalism and the biodiversity crisis all seemingly as bad as they can get – except they all keep getting worse locally and globally!”

“Food security has moved rapidly up the agenda with crop failures that were predicted to affect us in several decades now happening in multiple breadbaskets around the world. Here, prices of staples are starting to increase, but war and famine afflict poorer nations. We urgently need to become self-sufficient in food production to relieve the pressure of our imports on others’ harvests and to improve resilience. Here in NE Scotland, most of the arable land is used not to grow food, but grain for alcohol.”

“So back to this place and how we can help. This used to be the council’s plant nursery and over the last few years we have been developing a partnership with a voluntary group interested in growing food here. The site was entirely covered in fabric, resulting in very poor soil that is compacted and basically dead. It will be a lot of work to restore the soil.”

Produce in the poly tunnels, photo Campy Growers

“Meanwhile we use a lot of the locally-produced council compost for growing. We produce a lot of different vegetables such as beans, peas, carrots, sweetcorn, courgettes, squash, lettuce, beetroot, turnip and a LOT of kale! ”

“We have installed mesh over a tunnel frame to keep the pigeons off and this has made a huge difference to our crops this year. We have been giving away veg every Saturday through the summer and have attracted a lot of volunteers who want to help produce food for the city. ”

“But the real purpose of the Campy Growers’ project is to train and help people to learn how to grow their own food in their backies/gardens/local green spaces so that we can maximise local, free, healthy food production. ”

“Next season we will have two enormous polytunnels brought into production as well as a ScotGov-funded building that will serve as a base for training and growing. We hope that this can boost the city’s food production, resulting in healthier, more resilient, cheaper, ultra-local food becoming a way of life in Dundee.”

As Kate and Beverley took us around the plot and shared the most delicious Dundee made cakes and tea, the lively conversation that had begun at Kirklandbank with Marian and Antonia continued. The potential of increasing people’s wellbeing as a result of changing how we produce and consume food drew passionate agreement from many. “We know that if you eat healthy food and you hang out in nature and you talk to people about nice things, it will make you feel better. Plus we’re saving the planet with preserving biodiversity and improving the biodiversity in this place,” said one participant. The issue of educating people about food, which had been a theme throughout the day, came up again. “One of the things I would really love to see would be for schools to be twinned with farms. So that know that when they’re eating something, where it’s coming from, for the provenance to be really there” said another.

Beverley Searle from Campy Growers talking with George Oriahi from Scottish Enterprise, photo Clare Cooper

We ended our day clear about how the vision and possibility of initiatives like Campy will shape what will be on our plates in 2042: “Community gardens have the power to change society in so many ways – lots of people are scared about food security, lots of people are worried about the climate emergency, lots of people feel very disempowered,” said Kate.

“But community gardens give people the opportunity to do something positive about it. And positive engagement is empowering. Once people get a little bit of empowerment, they say ‘hang on a second we can do this for ourselves’. And that’s when they start demanding societal change through the ballot box. Community growing projects are so good for mental health they are so good for societal cohesion. They’re so good for addressing biodiversity. They empower on so many different levels. I think that this, this is how we start a gentle revolution.”

Resources

Scottish Government’s Good Food Nation Policy

Scottish Government’s Vision For Scottish Agriculture

Pointing The Way To A Scottish Organic Action Plan 2022: Work In Progress

The 2022 Bioregioning Tayside Learning Journey ‘Change The Frame: Change The Story‘ was supported by the Scottish Rural Network, Scottish Enterprise, the Rural Youth Project, NatureScot and the Collaboration for Bioregional Action Learning & Transformation.