Bioregioning Tayside’s latest and most ambitious project to date has been to begin working with Leon Seefeld of Dark Matter Labs to build Scotland’s first Bioregional Financing Facility. Read our interview with Leon below to find out more!

Leon Seefeld in the Austrian Alps

Leon Seefeld in the Austrian Alps

Tell us about yourself, Leon…

I grew up on the countryside of Northern Germany, surrounded by nature and from a young age deeply involved in community work. When I started my business and economics degree at Lancaster University and even later during my Master’s degree in systems thinking and complexity science in Sweden, I always knew that I would eventually put my time and skills to work for the things I learned to appreciate during my childhood.

Today, I work at the intersection of finance, nature, systems thinking, and novel business models. My focus is on designing regenerative financial and value flow systems that support ecological restoration and social resilience – at the bioregional scale. I’ve been fortunate to collaborate with visionary people and organisations worldwide, such as Dark Matter Labs and Bioregional Weaving Labs, exploring how capital can flow in ways that align with the rhythms of nature and the needs of communities. Broadly speaking, my work is about bridging silos—whether it’s between stakeholders, sectors, or disciplines—and creating structures that are both pragmatic and feel uneasy for those that are trying to preserve the status quo.

A burn in Glenshee, photo Clare Cooper

A burn in Glenshee, photo Clare Cooper

Can you explain what a Bioregional Financing Facility is?

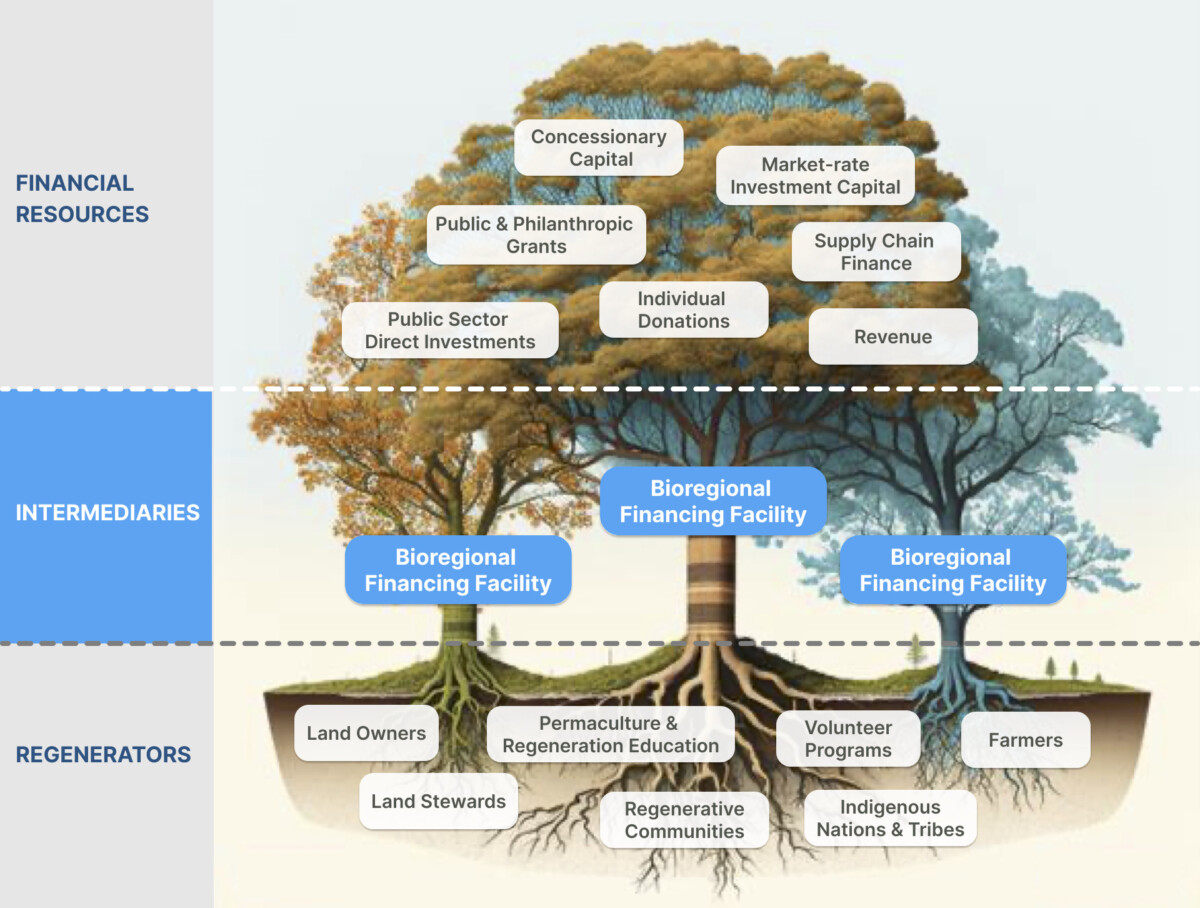

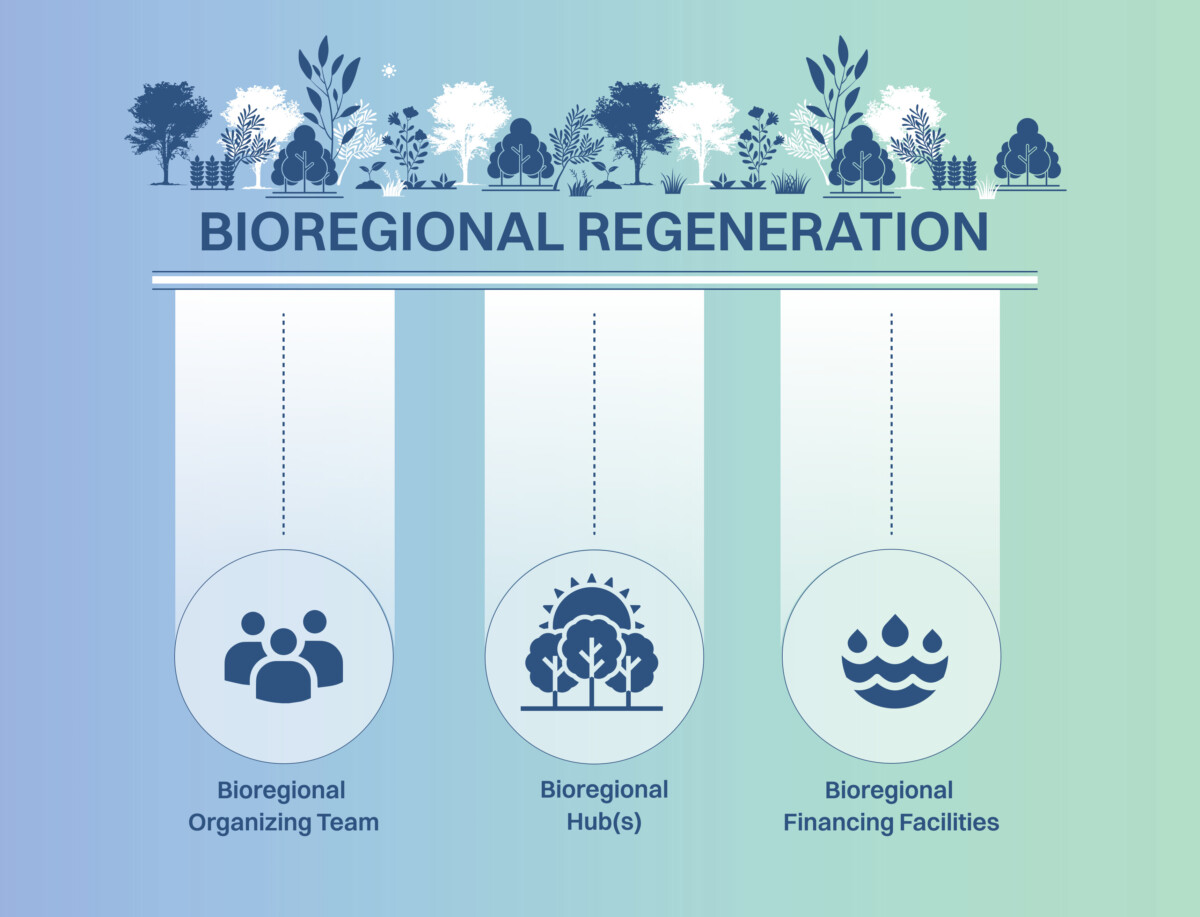

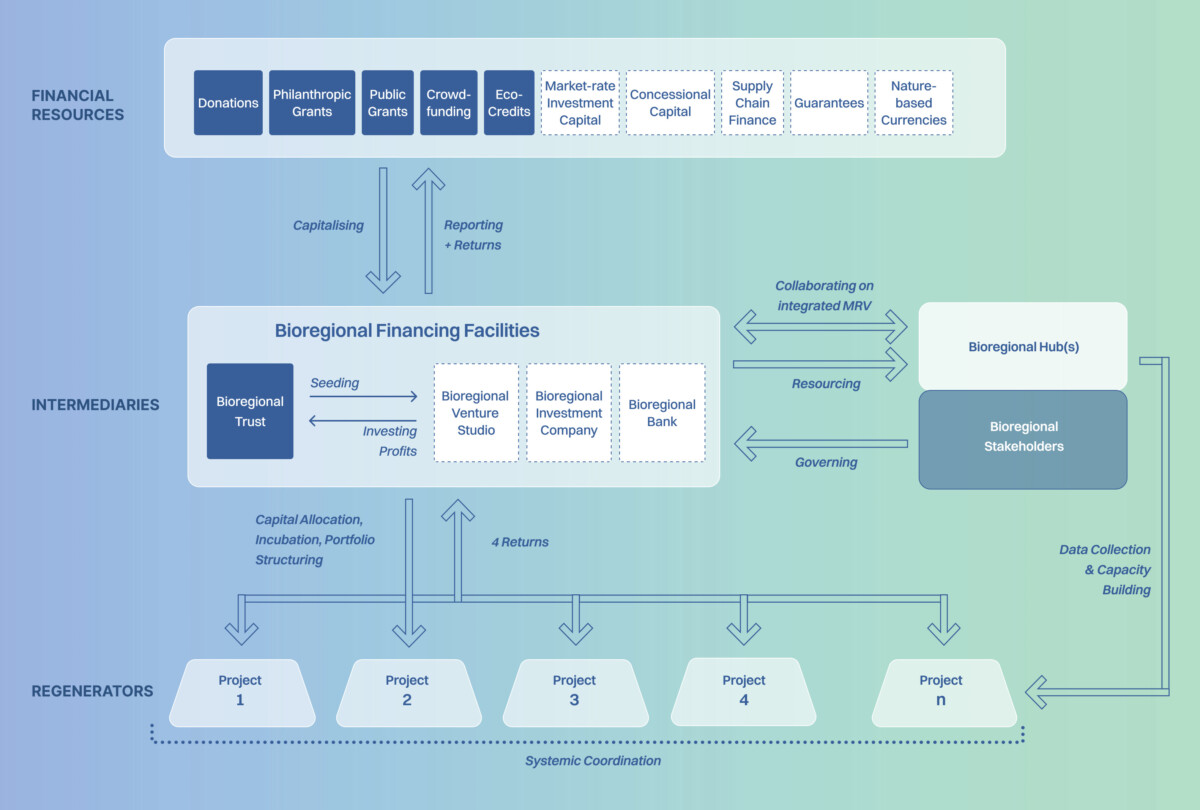

Bioregional Financing Facilities (BFFs) are a new layer in the global financial architecture that can help:

- drive the decentralisation of financial resource governance,

- design project portfolios for systemic change, and

- bring to life the transition to a regenerative economy at the bioregional scale.

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

They are emerging because as awareness and understanding of the polycrisis grows, and regulatory pressure increases, more and more actors from across the financial sector are beginning to direct financial capital towards supporting biocultural regeneration. And while on the surface this might seem promising, there is significant risk that if these resources flow through the existing financial architecture, they could lead to further commodification, privatisation, financialisation, and centralisation of natural assets and wealth. Therefore, closing the “nature finance gap” alone is not sufficient. Where those resources are spent, how financing is structured, and who gets to make those decisions is as important as the quantum of capital.

While a singular BFF can exist in isolation, they ideally become a deeply interwoven ecology of new financial institutions and instruments designed to direct financial resources toward regenerative projects and business cases within a specific bioregion. They act as a kind of connective tissue, bringing together communities, institutions, and investors to collaboratively resource and implement solutions that restore the vitality of ecosystems, address cascading climate breakdown impacts locally, and strengthen the resilience of place-based economies.

A rock hosting a multitude of life in Glenshee, photo Clare Cooper

A rock hosting a multitude of life in Glenshee, photo Clare Cooper

BFFs foster aggregation and coordination, allowing smaller, impactful projects to be bundled into larger, cohesive portfolios. This not only builds investment cases that attract institutional investors but also creates systemic synergy among projects, amplifying their impact through combinatorial effects. For example, integrating regenerative agriculture initiatives with watershed restoration and community-led renewable energy projects allows for multi-solving at the portfolio level and generates mutually reinforcing benefits across the ecological, economic, and social dimensions of the transition.

BFFs also shift power dynamics by restoring governance to local people. Communities that live within the bioregion understand its challenges and opportunities better than external actors. By empowering these stakeholders directly to make allocation decisions, BFFs ensure that investments are directed toward initiatives that align with local priorities and context-specific ecological realities.

Simply put, BFFs are about creating a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities within a bioregion and mobilising capital in ways that reflect ecological and social priorities of place. I honestly believe it is important to not solely think of BFFs as funding mechanisms—but also as governance systems, capacity-building tools, and mechanisms for accountability.

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

What is their potential? How can they move us on from the ‘business as usual’ that is preventing us from restoring and regenerating nature?

From my perspective, the immense potential of BFFs lies in their ability to shift both the narrative and practice of finance. The flow of finance, for good or for worse, is often compared to the blood system in a body or water cycles in nature. The force that connects everything and circulates nutrients, antibodies, and other elements essential for life. Business-as-usual approaches that are focussed on extraction, short-term gains, power-over relationships, and disconnection from local realities are currently causing more harm than good. Our bioregional immune system is increasingly challenged by the pollution and disparities that these flows of finance foster. I see potential for BFFs to catalyse inherently circular flows of finance that spread health and build resilience.

Through their new approach to governance and allocation, BFFs will shift our relationship with finance and allow people to feel a sense of agency. Which, in turn, can create a powerful pull effect for mass-engagement in bioregional regeneration.

Funding the types of projects that conventional finance often overlooks—such as rewilding initiatives, soil restoration, or community weaving and trust building—is almost only the surface level added value in this. On deeper levels, I foresee BFFs to help fundamentally recode our perception of ‘value’ and to normalise multi-capital accounting systems that recognise systemic returns beyond the financial. BFFs will help us build new economies and capital markets around real value and those things that are actually important in this time of collapse.

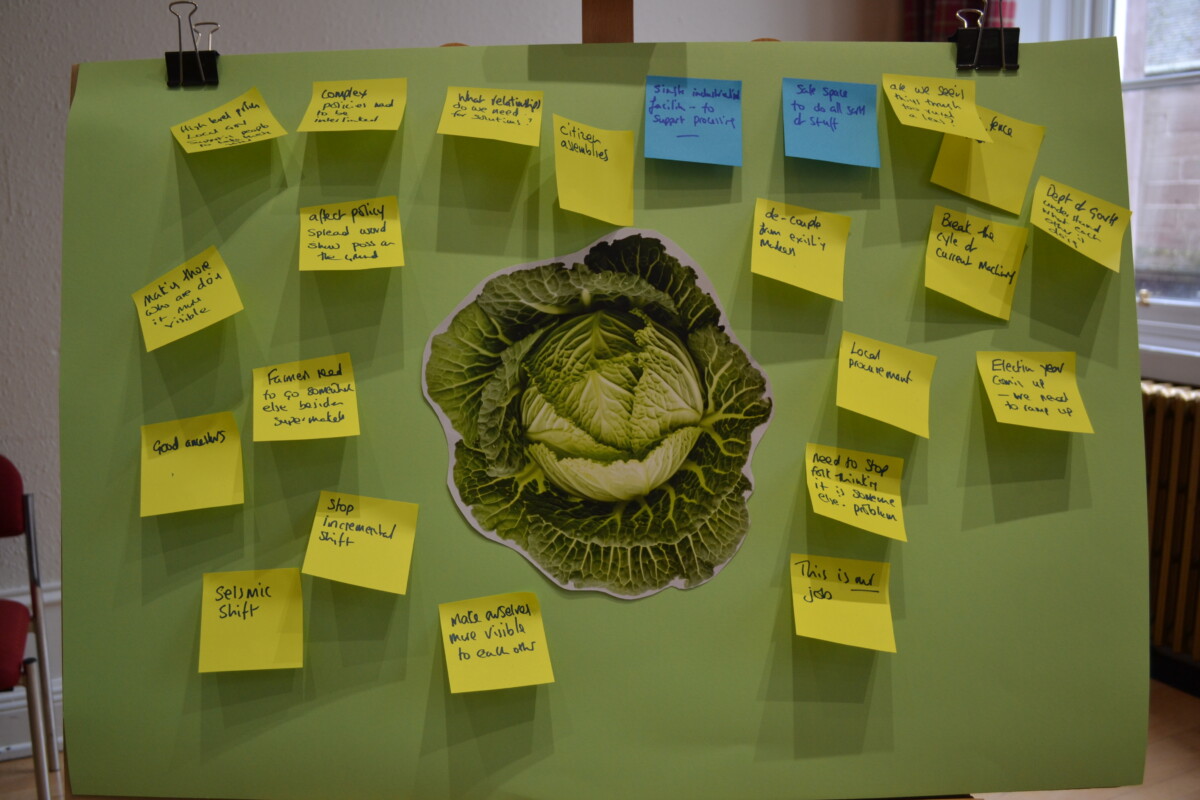

Snapshot from one of Bioregioning Tayside’s workshops introducing Strategy Games to stakeholders in the River Ericht Catchment Restoration Initiative, photo Clare Cooper

Snapshot from one of Bioregioning Tayside’s workshops introducing Strategy Games to stakeholders in the River Ericht Catchment Restoration Initiative, photo Clare Cooper

Why do you think the Tay Bioregion might be fertile ground to build a BFF?

Tayside is strategically important for Scotland, both economically and geographically. In the current economic paradigm, it is recognised for its significant skills, innovation and experience in tech, life sciences and medicine, agriculture and tourism. Geographically, it holds the largest water catchment in Scotland, the Tay. In a likely future economy, which will be driven by increasing digitalisation, urgent responses to the climate and biodiversity crises, and security concerns, it has the potential to build on its existing world-leading research expertise in food, energy and water security, whilst its rich natural and cultural heritage offers opportunities to develop new approaches to rural re-population and sustainable livelihoods that are more suited to navigating future challenges. Now, that’s a sentence you’d normally only find in the German language. But it actually quite nicely reflects the complexity we’re dealing with when looking at bioregions as whole places that hold both value and risk across past, present, and future.

It is in these tension spaces that opportunities for great things emerge. Addressing its vulnerabilities by spearheading the development of the next generation of place-based financial institutions, sounds like one of those extraordinary opportunities for Tayside.

BFFs depend on a strong bedrock of community organising and mapping & analysis. Bioregioning Tayside, through all of its activities to date, has, along with others, been part of laying this important foundation. A strong portfolio of projects and project ideas is growing from deep relationship building and collective deliberation. It is not least the incredibly caring approach to the work and relentlessly systemic mindset of the people behind BT that makes me really hopeful about an inspiring example of BFFs emerging in Tayside soon.

Snapshot from one of Bioregioning Tayside’s workshops looking at how to strengthen and develop community-led food growing, photo Clare Cooper

Snapshot from one of Bioregioning Tayside’s workshops looking at how to strengthen and develop community-led food growing, photo Clare Cooper

There are other Bioregions in the world that are building them too. How are they the same/different?

Every bioregion is unique, shaped by its ecosystems, cultures, and histories. That said, the principles underlying BFFs are consistent: they decentralise financial resource governance and are place-based, systems-oriented, and aimed at regeneration. What varies is the emphasis. For example, in tropical bioregions, BFFs might focus heavily on directing financial flows toward combating deforestation and restoring mangroves, while in Europe, there might be more emphasis on regenerative agriculture and watershed management. The quantum and quality of financial capital as well as its sources will depend on the diversity of local funding opportunities and the access to global capital markets.

While based on the same principles, the governance structures also differ. In some bioregions, Indigenous values and leadership play a central role; in others, the focus is on forging partnerships between private and public sectors. I find that learning from all these diverse approaches helps inform what is possible in a specific context like Tayside.

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

Illustration from the book: Bioregional Financing Facilities – Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet

What’s the route map to building a BFF with us here in Tayside?

We have just concluded a comprehensive stocktake of the foundational elements present and missing in Tayside that would allow BFFs to be most effective and efficient. As we speak, the plans for 2025 are being made to move from stocktake to filling the gaps and beginning to build early iterations of the Tayside BFFs.

My hope is that we can publish our plan for 2025 early in the year. Because the work is highly emergent and uncertain, it is pretty clear that we will have to start with relatively small pilots that allow us to build trust with various stakeholders and prove the concept of a Tayside BFF. Those pilots will help us tap into what might be described as the “adjacent possibles” of where Tayside is today. From there, we can start to build into future horizons that begin to rethink and radically recode the possible. Initially, we will need to create value flow maps and identify synergistic project portfolios that can absorb financial capital. We will map potential flows of capital supply and its conditions. We will need to evolve and establish new governance structures and frameworks for measuring success.

The process will be iterative and characterised by continuous learning and adaptation. It’s going to be an exciting journey!

Looking north across Strathmore with the Keillor Standing Stone in the foreground, photo Clare Cooper

Looking north across Strathmore with the Keillor Standing Stone in the foreground, photo Clare Cooper

What would you like to see our BFF achieving in 3, 5, 10, and 50 years’ time?

In the uncertain and highly volatile times we live in, I find it difficult to imagine what is going to happen in 10 let alone 50 years. But I am actually quite hopeful about some accelerated developments happening in 2025 and 2026. The bioregional movement is gaining lots of traction and even the discussion around bioregional finance appears to make larger and larger waves. Thus, I think it is totally possible to have a first portfolio of pilot projects underway, that demonstrates bioregional value creation and is financed through a bespoke mechanism akin to BFFs. It will be important to build the base layers of the new allocation governance structure and to establish partnerships with financial and regeneration actors that inspire confidence among a wider community of stakeholders.

Over a 5 to 10-year time horizon I hope we begin to see ecosystems returning to vitality as a consequence of altered finance allocation decisions and communities regrowing their trust and resilience in face of the coming hardship.

In the long-term I wish for the BFF to be an enduring ecosystem of institutions and mechanisms, with their successes embedded in cultural and ecological memory.

Hair Ice Fungus (Exidiopsis effusa) in the Den O’ Alyth, photo Clare Cooper

Hair Ice Fungus (Exidiopsis effusa) in the Den O’ Alyth, photo Clare Cooper

Who has inspired you to work on BFFs?

What a great question! While I’m not sure it was a particular person but more the necessity of the mission itself that inspired me to do this work, I obviously draw great inspiration from renown systems thinkers like Donella Meadows, our teams at DML and BWL, and systemic finance pioneers like the team of Hawai’i Investment Ready. But I’m equally inspired by grassroots leaders—Indigenous communities, farmers, weavers, and activists—who are leading the regeneration of our planet and communities with their hands in the soil and heart in the relationships, every day. They remind me that this work is ultimately about people and connection, as much as it is about systems and finance.

You can read the book Leon co-authored on Bioregional Financing Facilities here.

This entry was posted in News